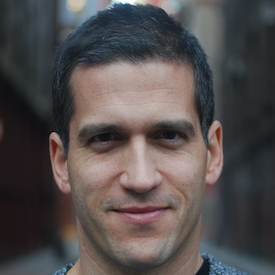

Catherine Bracy is the Founder and CEO of TechEquity, an organization working at the intersection of tech and economic equity. The company advocates on behalf of policies that ensure people—not companies—control how technology shapes their economic futures. She was previously Code for America’s senior director of Partnerships and Ecosystem, and founded Code for All. During the 2012 election cycle, she was director of Obama for America’s Technology Field Office in San Francisco.

What’s the big idea?

Venture capital isn’t just funding innovation; it’s shaping what kind of innovation is possible. Right now, that system is failing us. It forces startups to sacrifice real problem-solving and innovation for the sake of chasing unsustainable growth. Our economy will be better off if we create and rely on a startup ecosystem that rewards real value rather than speculative hype.

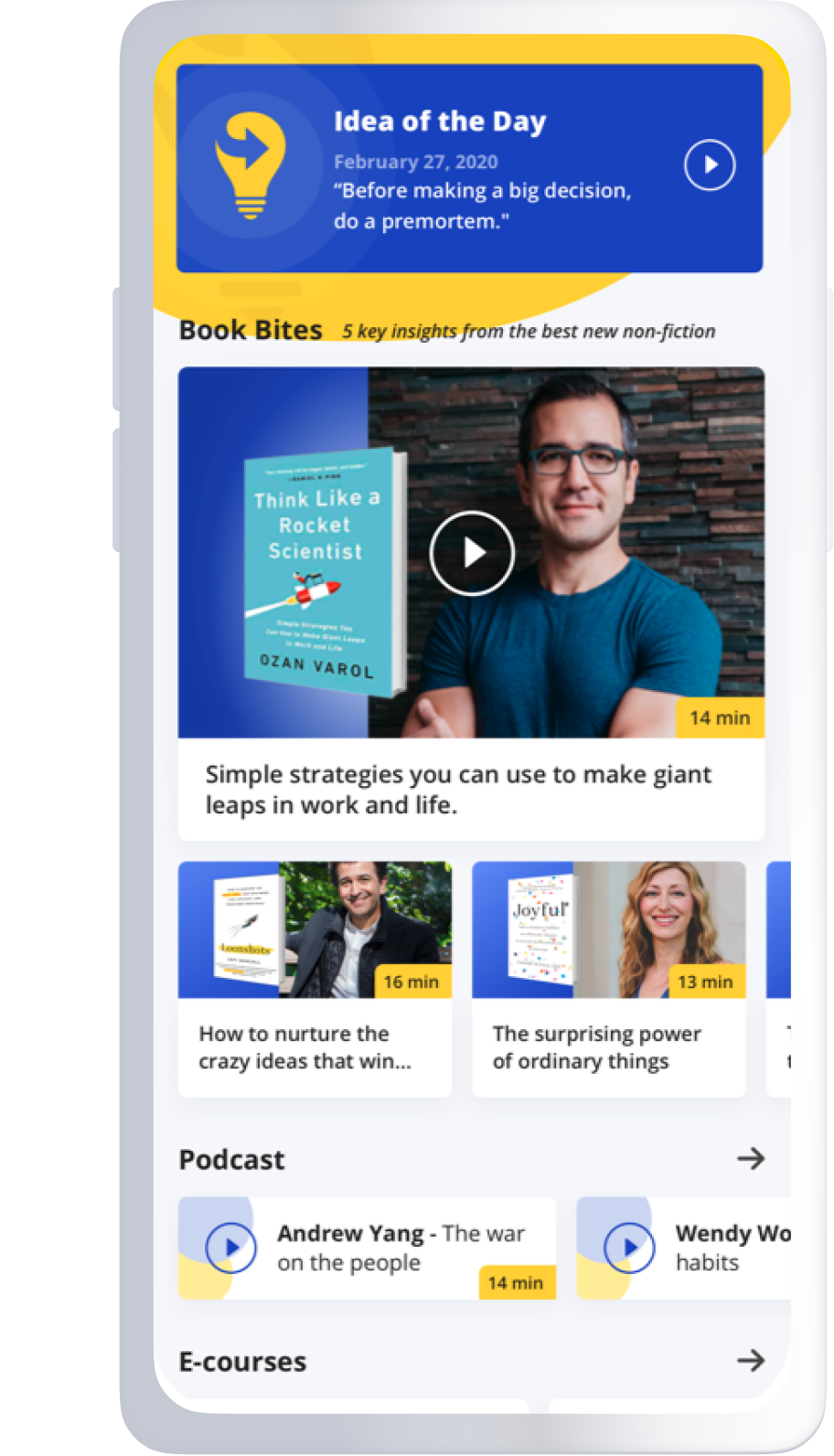

Below, Catherine shares five key insights from her new book, World Eaters: How Venture Capital is Cannibalizing the Economy. Listen to the audio version—read by Catherine herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Technology isn’t the problem. Venture capital is.

A few years ago, I was in a strategy session with labor advocates who were trying to get gig companies (Uber, DoorDash, and the like) to treat their workers better. It was a room full of smart, committed people with great ideas about how to create fairer wages, better protections, and a pathway for these workers to have more stability. As we talked, something clicked for me.

We were strategizing ways to convince these companies to change—but at what point in their growth cycle could they have made better choices? When they were tiny startups, just trying to survive, they had no time to think about worker protections. Then, seemingly overnight, they became billion-dollar global giants—except by then, their exploitative business models were too big and too profitable to unwind.

“Venture capital demands exponential growth fast.”

This struck me as different from how industries used to grow. Traditionally, companies had middle stages: periods of stability where they could adjust their practices, adapt to regulations, and build systems that worked for both employees and society.

But tech doesn’t work that way. Some of that has to do with software itself because it’s cheap to build, easy to scale, and can reach millions of users almost instantly. But most of it has to do with the economic incentives behind the companies—and that structure is venture capital.

Venture capital demands exponential growth fast. There’s no pause button. No moment where a company can afford to step back and say, How do we do this more responsibly? In the venture model, companies aren’t built to be stable. They’re built to scale or die.

As Charlie Munger said: “Show me the incentives, and I’ll show you the outcomes.” The economic outcomes we’re living with today—the erosion of worker protections, skyrocketing housing costs, and the growing concentration of wealth in fewer hands—aren’t accidents. They’re a direct result of the incentives baked into venture capital.

2. The Power Law is shaping the economy in ways you don’t see.

The Power Law is a statistical principle where a few extreme values dominate the dataset. Think earthquakes: most are tiny tremors, but a few are catastrophic.

Venture capital portfolios follow this same pattern. Investors spread their bets across dozens of startups, expecting just one or two to hit it big while the rest fail. These extreme successes are called unicorns in the parlance of Silicon Valley.

“Think earthquakes: most are tiny tremors, but a few are catastrophic.”

That might sound like a reasonable strategy since startups are risky. But here’s where it gets dangerous: As venture capital evolved, the Power Law went from being an observation of how venture capital funds look as a result of pursuing these risky companies to a guiding force for how investors should invest.

In other words, instead of pursuing breakthroughs and achieving Power Law distributions as a natural result, venture capital became about pursuing Power Law distributions without any regard to the kind of company that was creating it. It doesn’t matter whether a business is solving a real problem, whether it’s good for society, or even whether it’s profitable. What matters is scale. This is why we see:

- Monopolistic tech giants instead of diverse, competitive markets.

- Growth-obsessed startups that burn through billions with no clear path to profitability.

- Essential services—like housing—being financialized to fit a Silicon Valley growth narrative.

Venture capital started as a way to fund technological breakthroughs. But now, it’s become a system designed not to create value, but to chase billion-dollar valuations at any cost. That cost is one that the rest of us are asked to bear.

3. Venture capital destroys more value than it creates.

Because venture capitalists do not know which startups will be their unicorns, they force every company they invest in to chase billion-dollar growth—whether or not it makes sense. That means:

- Exploiting workers to cut costs.

- Shipping half-baked products just to scale faster.

- Skirting regulations to stay ahead of slower-moving competitors.

- Committing fraud—or at least getting very, very close.

The tragedy is that many of these companies could have been solid, sustainable businesses. But because they were forced to chase unrealistic growth, they collapsed. Great ideas get destroyed not because they weren’t good businesses, but because they weren’t venture capital businesses.

Take LocalData, a startup that helped cities manage property data to increase revenue and prevent blight. It was profitable and growing. But because venture capital investors didn’t see it as a billion-dollar opportunity, they pressured the founders to pivot to a different market. The pivot failed and the company shut down. This isn’t just one company’s story. It’s the story of an entire ecosystem that rewards financial engineering over real innovation.

4. The problem isn’t the companies that venture capital funds—it’s the ones it doesn’t.

If you are an entrepreneur with a great idea that doesn’t fit the venture model, you have two choices:

1) Take venture capital money and distort your business to chase growth you can’t sustain.

2) Get no funding at all.

This is especially dangerous in markets like housing and clean energy, areas where we desperately need innovation but where venture capital’s demand for hypergrowth doesn’t fit.

Venture capital doesn’t just fund bad businesses. It crowds out the good ones, siphoning capital away from sustainable solutions and into the next speculative bubble. If we want innovation that solves problems, we need new funding models that aren’t beholden to the Power Law.

5. It’s time for the Indie Era of Startups.

When I started writing World Eaters, I thought it would be mostly about how venture capital is harming society. But as I talked to entrepreneurs trying to build differently, I realized the story was bigger than just what’s broken.

There are founders who want to build companies that are profitable and sustainable—who reject the unicorn model in favor of something more resilient. There are investors experimenting with alternative funding models that reward long-term success rather than short-term hype.

“We can build a startup ecosystem that rewards real value, not just speculative hype.”

These are companies like Butcherbox, whose founder—who had soured on venture capital after venture capitalists killed a previous business of his—got his startup capital from a crowdfunding campaign. Butcherbox is now a $500 million per year business with the time and space to take on efforts to improve jobs in the meatpacking industry and support sustainable ranching.

Now is the perfect time to help businesses like this succeed. With higher interest rates, the market is shifting. Investors can’t throw unlimited cash at money-losing businesses anymore. Companies must prove traction earlier. That means we have a window (before the next bubble inflates) to show that another way is possible.

If we do it right, this could be the moment where the Indie Era of Startups begins. Entrepreneurs, investors, and policymakers don’t have to accept the Power Law as destiny. We can build a startup ecosystem that rewards real value, not just speculative hype. If we get it right, we won’t just fix tech—we’ll fix the economy.

To listen to the audio version read by author Catherine Bracy, download the Next Big Idea App today: