For decades, urban planners have blanketed our cities with the cheap and convenient car storage known as parking. They’ve swapped sidewalks for strip malls and bulldozed bright, inviting storefronts to make room for dark, urine-scented parking garages. In some downtowns, more land is now devoted to parking than buildings.

Parking profligacy has left us with cities that are polluted and hostile to pedestrians; they’re also increasingly unaffordable because legally required parking can drive up the cost of residential construction by 25 percent.

In Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World, journalist Henry Grabar dares to imagine a future in which we knock parking off its pedestal by enacting new laws, adopting new attitudes, and embracing new technologies (like e-bikes and autonomous cars) that make our cities greener, friendlier, safer, and more fun.

Sign up for The Next Big Idea newsletter here.

Rufus Griscom: We’ve torn down buildings in cities like Denver and Los Angeles and all across America to make parking spaces. And we adopted building codes that radically changed the architecture and increased the cost of building residences and commercial properties.

Henry Grabar: This is the big hidden decision that gets made in the American city at mid-century that winds up shaping a half century of urban development in this country and even determines the look and feel of our cities today. Faced with this crushing shortage of parking relative to the number of people who are buying automobiles in the post-war era of prosperity, American cities make a decision that every new or renovated building will have to include a certain amount of parking.

What followed from that was 70 years of suburban building codes determining the shape of the urban environment. The first consequence is that most historic structures in most American cities wind up getting torn down because they cannot be put to new use without providing a sufficient amount of parking. I talked to an architect in Ann Arbor, Michigan, who told me that she had worked with owners who had described buildings as having a “parking padlock” on their doors. It looked like a nice property that you might be able to adapt and turn into a new cafe or a brewery or bookstore, but, in fact, you couldn’t do any of that stuff because there wasn’t enough parking.

As a result, everything built before the 1940s becomes technically obsolete as far as the code is concerned, so more buildings got torn down to make way for parking lots.

Rufus: Another negative consequence is that building parking spaces is dramatically more expensive than I would have guessed. One data point you have is that parking for each car costs roughly twice as much of the value of a typical automobile. And so if you decide you want to build a new condo development, you end up with fewer units and a higher price for each apartment. It has a devastating impact on the expense of living in so many of these cities.

Henry: I looked up a 2023 construction survey on the cost of new parking, and it put the median parking space in the United States at $27,000. Now, that’s a lot of money on the face of it, but keep in mind that’s also a national average. That number is much higher in the place where the cost of living is high or where parking has to be built underground.

“If you don’t drive, you are paying 10 to 30 percent of your rent on a parking space that you’re never going to use.”

Now, let’s go back to the question of new buildings built under the parking codes that took shape in the latter half of the 20th century. Let’s take an apartment building, for example. It became standard to include two parking spaces for every unit. This basically makes it impossible to build many of the vernacular urban housing types that had characterized American cities leading up to World War II. I’m thinking about things like bungalow courts in Los Angeles or triple deckers in Boston or three flats in Chicago. All this stuff becomes impossible because there’s simply too much parking required. These types of housing typologies go extinct and the housing that does get built contains a large amount of parking, and that drives up costs. Surveys have shown it accounts for anywhere between 10 and 30 percent of the rent in some new projects that have structured parking included. That is a massive expense, and it’s required by law. That’s not something the tenants are given a choice about. So if you don’t drive, you are paying 10 to 30 percent of your rent on a parking space that you’re never going to use.

Rufus: Among the solutions, one of the most obvious is abolishing parking minimums from the building code.

Henry: This has caught fire since I started working on this book. In the last six years, we have seen the first big cities—places like Buffalo, Hartford, and San Francisco—decide to get rid of their parking codes. This is a tremendous step.

I think there are two things motivating these reforms. The first is the cost of housing. The housing affordability crisis is a generational challenge, the likes of which we have not seen in many decades, and parking stands in the way of creating more housing and especially more affordable housing. The second is climate. And the realization that parking is. Connected at the hip to driving. And the more parking you build, the more people will buy cars and the more they will drive them. And so if you’re interested in either reducing greenhouse gas emissions or reducing local pollution and all the other externalities that are tied to driving, then you really have to stop requiring parking.

Rufus: Let’s turn to the promise of the potential of autonomous driving of self-driving cars. It may take longer than we think, but the implications of having cars drive themselves could be pretty profound for parking and for the urban experience.

Henry: I first heard about this idea in a blog post written by one of the founders of Lyft, the ride sharing company, and he was suggesting that if autonomous vehicles became commonplace, one of the consequences would be an enormous devaluation of all this high-cost center city parking. You would simply have no reason to pay for that parking anymore. Your car could drop you off at work and then drive a couple miles, get to a low-cost parking spot, and sit there for the day.

“The more parking you build, the more people will buy cars and the more they will drive them.”

The question becomes: What do you do with all that parking space? You could turn it into housing, you could turn it into parks, you could turn it into anything. The potential is somewhat dizzying.

Rufus: Think of the efficiency of a car. If it’s only for one person, it can be a smaller car. If you have a group of friends going out, maybe it’s an autonomous party bus. You can have a wider variety of more efficiently sized vehicles that drop you off where you want to go, then go and pick up other people. The potential to free up this astonishing amount of space—often 10, 12, 15 percent of American downtowns—for other purposes is potentially pretty exciting.

Henry: I’m really glad you mentioned the idea of right-sizing vehicles. One of the reasons people buy big cars is because they have in mind that one trip is going to require all seven seats. If you manage to take that concern away by saying, Look, this is going to be available to you when you need it, then I think you free up room for people to make more reasonable decisions about what they need for their daily trips. That, again, creates an opportunity for different kinds of parking arrangements, different kinds of streets and different modes of vehicle ownership.

Edited and condensed for clarity.

You May Also Like:

- Elise Hu shares five key insights from her book, Flawless: Lessons in Looks and Culture from the K-Beauty Capital

- Henry Grabar shares five key insights from his book, Paved Paradise: How Parking Explains the World

- Rupert Callender shares five key insights from his book, What Remains?: Life, Death and the Human Art of Undertaking

- Jamie Loftus shares five key insights from her book, Raw Dog: A Naked History of Hot Dogs

- Felix Gillette and John Koblin share five key insights from their book, It’s Not TV: The Spectacular Rise, Revolution, and Future of HBO

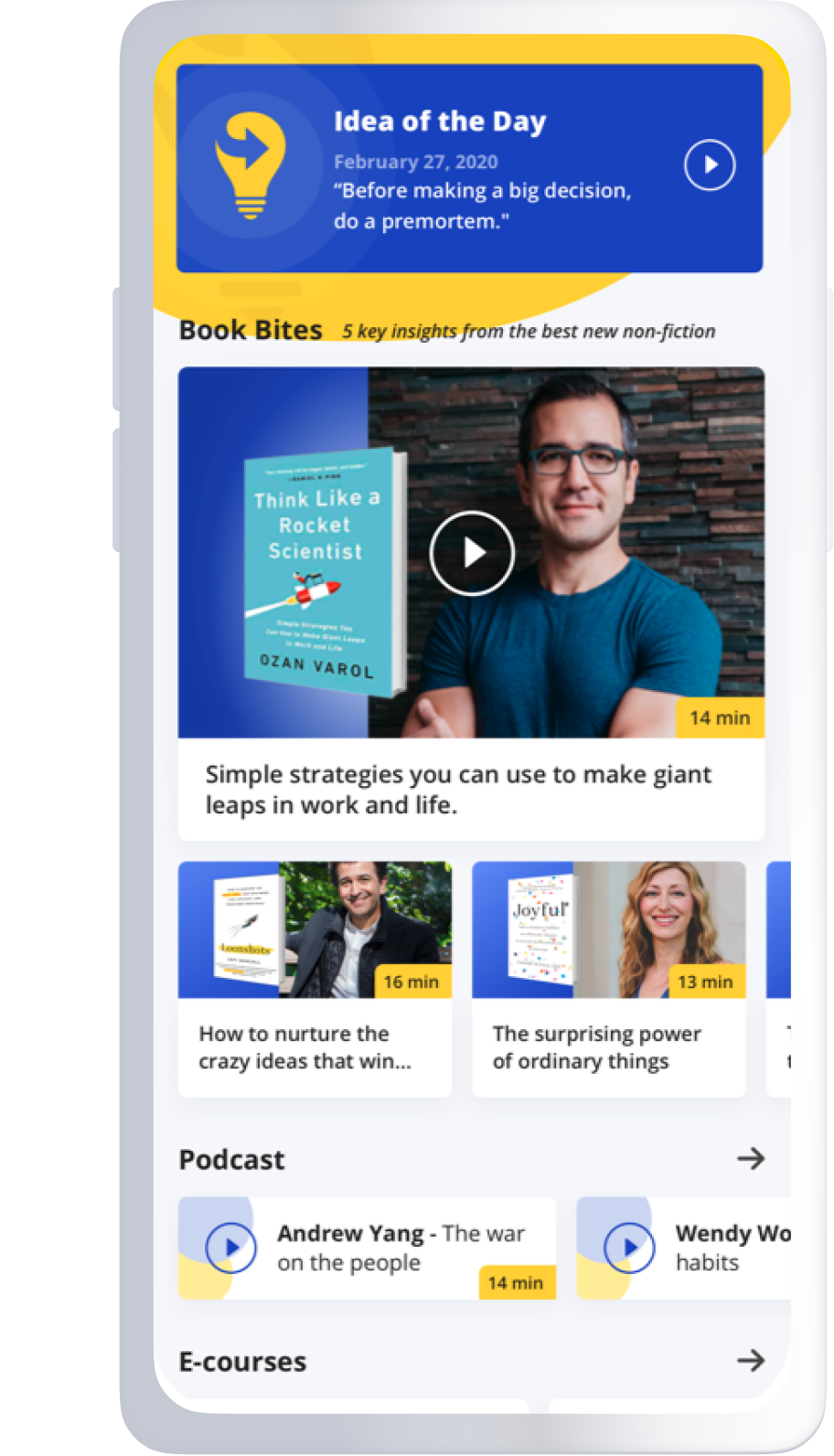

To enjoy ad-free episodes of the Next Big Idea podcast, download the Next Big Idea App today: