Elizabeth Earnshaw is a certified marriage and family therapist and the founder of A Better Life Therapy. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, and the Washington Post. She is also the author of I Want This to Work.

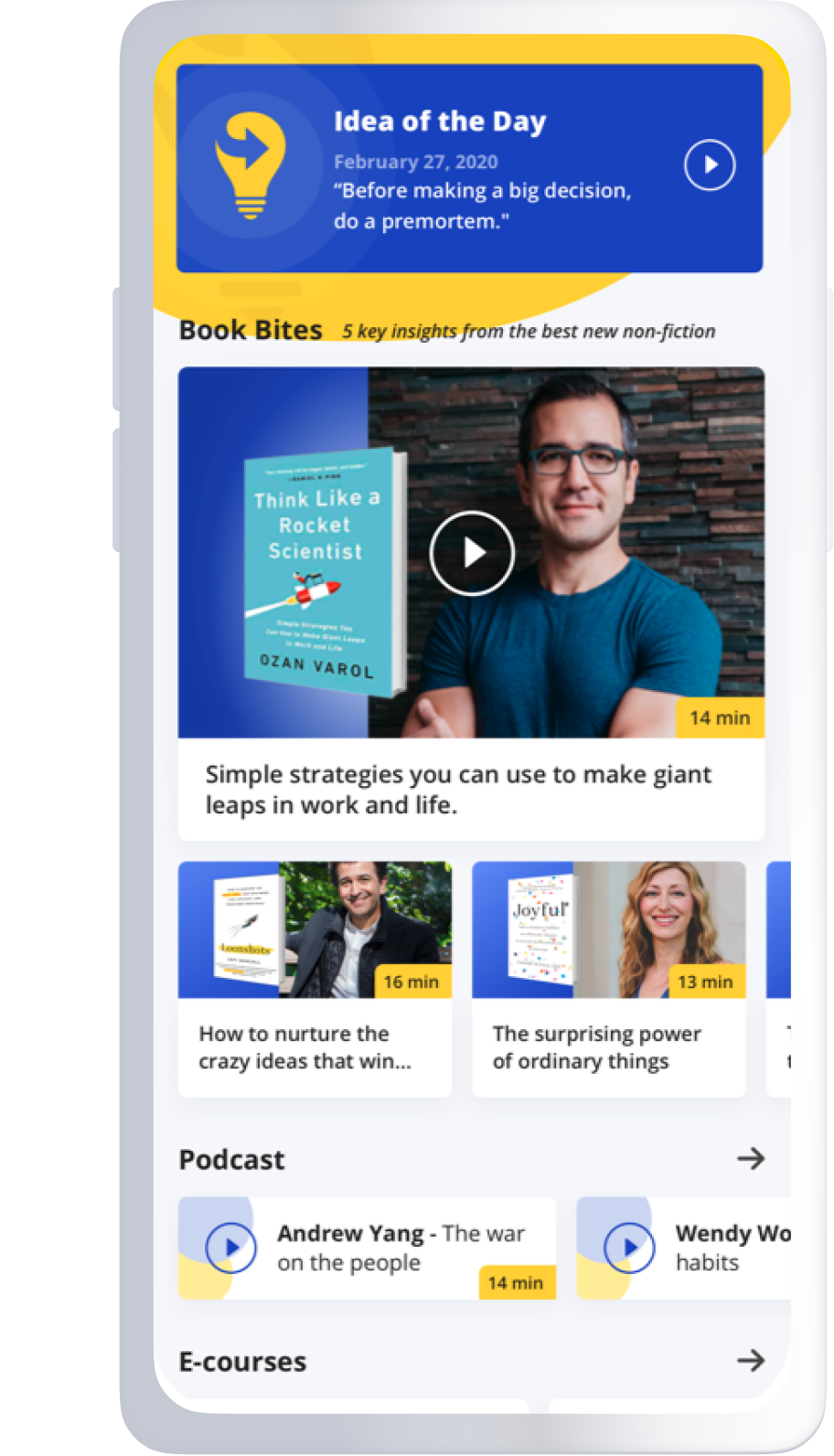

Below, Elizabeth shares five key insights from her new book, ‘Til Stress Do Us Part: How to Heal the #1 Issue in Our Relationships. Listen to the audio version—read by Elizabeth herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. It’s not you, it’s the stress.

Couples often come to my office confused about why they are fighting so much. These are people who love and respect each other, but just can’t seem to get along in daily life. Some describe themselves as withdrawn from each other. Others say they experience frequent verbal arguments. Some couples describe a mix of both, such as a dance of yelling at each other only to retreat to their rooms, avoiding further contact. These couples blame many things: their partner’s upbringing, lack of communication skills, or an incompatible attachment style. These factors can influence how people get along. However, I often see a different culprit: stress.

Studies show that stress reduces our ability to connect with our partners because of how it impacts both our physiology and mind. When under stress, the body sends adrenaline and cortisol throughout the system. These hormones increase heart rate. A heart rate of 100 beats per minute or more impacts internal organs (have you ever noticed that you need to pee more when you’re nervous?) and signals to the brain that we’re unsafe. Because of these signals of threat or danger, the brain starts to think differently. A person under stress begins losing relational capacities like humor, affection, curiosity, listening skills, and problem-solving. This makes sense for the original intended purpose of a threat response. It’s not helpful to laugh at a joke, for example, if a lion is chasing you. However, these responses can be problematic in relationships.

As people bear the burden of external stressors to the relationship (like endless traumatic news cycles, fear of layoffs, and rude neighbors) and stressors within the relationship (like disagreements about finances or a lack of intimacy), couples can get trapped in a chronic stress state. This means they will be less likely to respond to their partner gracefully and more likely to focus on negative attributes. To change the impact of stress on a relationship, it’s essential to recognize who the real enemy is—endless stress—and team up with your partner as allies against the foe rather than each other.

2. Your nervous system gets the first word.

A few years into Katie and Jim’s relationship, Jim lost his job, which put them in a predicament. Their expenses were greater than their suddenly one-income household could bear. Immediately, both Jim and Katie felt stressed and began responding from a place of fear. Jim became withdrawn and aloof, and Katie became argumentative and critical. She blamed Jim for his lack of foresight and often paired a dramatic roll of the eyes with her comments about his nonexistent backup plan. Jim couldn’t see the fear beneath her words and expressions but felt his own. His fear and shame created an inner threat response, leading him to retreat to the basement and play more video games. It was too overwhelming even to consider how to climb out of the hole he felt he had fallen into.

“Each partner has a job to remind their partner’s nervous system that you’re safe with me.”

As Katie and Jim continued to manage the loss of Jim’s job this way, they grew further apart, creating inaccurate and negative narratives of each other in their own minds. They could never sit down together to discuss the issues at hand, face the problem together, and come up with a game plan. Like many couples, Katie and Jim didn’t know that their reactions were related to stress. Their narrative was that Katie was mean and Jim was lazy. They pointed fingers at each other rather than addressing the root cause of their financial issues. If Katie and Jim understood their nervous systems, they could pause, self-soothe, and offer soothing words.

To move forward, Katie would need to recognize that Jim’s nervous system needed support and reassurance, and Jim would need to know that Katie needed the same. When Katie criticized Jim, it told his nervous system that he was unsafe. And when Jim disappeared to the basement, it told Katie’s nervous system that she was unsafe because he abandoned her. Each partner has a job to remind their partner’s nervous system that you’re safe with me. This helps the body move into a relaxed state and our ability to see the big picture and communicate returns.

3. Mind the gap.

My husband Andrew and I piled a lot on our plate in our first few years of marriage: a dog, a child, a house, and a business. We tried to maintain our hobbies, health, and friendships but kept adding more. Andrew joined a wedding band, and I started sharing relationship advice online. I volunteered with a mental health organization and hired new employees for my practice. Living in Andrew’s hometown meant endless social opportunities for him. He was invited to join a local recreational softball team with his high school friends, and I encouraged him to do it.

He asked, “Are you sure? I know you’ve been struggling and that you’re really tired.” I smiled and nodded, saying, “I’m sure it’s going to be good for you.” So, twice a week, Andrew would come home, give me a kiss, throw on his softball gear, and run out while I seethed. But I’d ask myself, why am I so upset? This is who we are. We support each other’s hobbies.

Over time, I started blaming everything on his time away, his friends, and even softball. It made me less inclined to spend time with him and his friends and less interested in watching the games. I knew it was time to take inventory of my contributions to the problem. Was it really his friends’ fault? Probably not. In fact, it was the gap between what we value, wish for, and believe in and what our reality can support.

“To force a bridging of the gap, we often spend time, money, and energy that doesn’t serve us.”

While I wanted to be the supportive wife, I just couldn’t be that person. Our fast-paced society has inundated us with the idea that we can have everything and do everything if we only try hard enough. This has resulted in stressed families who feel they’re never good enough. Many of us believe there must be some recipe to fill the gap between how much money we have and how much money we want or between how much time we need to spend working and how much time we wish we could offer our spouse, but there’s no magical recipe.

To force a bridging of the gap, we often spend time, money, and energy that doesn’t serve us. But deciding not to bridge the gap means sacrificing something we want but can’t have. When we do the former, we tend to stress in the long term, and our relationships get the brunt of it. When we do the latter, we feel stressed in the moment, but we find more peace, fulfillment, direction, and simplicity down the road. Choosing to sacrifice might cause feelings of grief and disappointment or make other people angry. I call these sacrifices intentional sacrifices because we must make a conscious choice to sacrifice one thing to enjoy another and save our sanity.

There are so many stressors in life that we cannot control, and it’s important to take control where we can. One of those places is learning to identify where you’re pushing yourself too hard to build a bridge between the gaps. To prevent endless attempts at bridging the gaps, we must identify our values and goals so that those orient decision-making in relationships.

4. Choose where your energy goes.

Andrew and I were plopped in front of the TV after a long day at work. The news was blaring on screen, but we were not paying attention. Instead, we were glued to our much more captivating phones. We craved connection, but we weren’t prioritizing it with each other. Instead, we were finding it everywhere else: connection to world news, to strangers on Instagram, to our jobs through the Gmail app, and friends through iMessage. Suddenly, I wanted to connect with Andrew. I looked up and scoffed, “If we’re going to sit together, can you at least put your phone away?” Andrew, frustrated, replied, “You’ve been on your phone the entire time. I just picked mine up because you had yours.”

I knew he was right. I wasn’t managing my phone use well. When I get tired, I just want to scroll, but I know it does nothing for me. Our phones feel like another partner in the room, one we compete with for attention. I told him, “You’re right. What should we do instead?” We decided to watch a show together, placing our phones in a different room. We were tired, so we didn’t need to talk or do anything active. Just being together with our shared attention was enough.

Protecting relationships from time, emotional, financial, and physical energy drains is an important commitment. This provides a type of buffer that Stan Tatkin, the founder of the psychobiological approach to couples therapy, calls the couple bubble. It’s a protective cocoon that shields partners from stressful outside elements. Many couples pierce their cocoon with poor boundaries, weakening their relationship. These forces are called thirds. Thirds can be anything that threatens your connection by draining energy, resources, and trust. It could be hobbies, in-laws, the workplace, substances, friends, etc. We must identify and manage these thirds because it empowers us and strengthens our bonds. When we’re not managing our thirds, we create more stress between us as partners while also being inundated with stress from everywhere else.

“Thirds can be anything that threatens your connection by draining energy, resources, and trust.”

Managing thirds means working together to protect your relationship from all the things on the outside that can burden us. It’s about prioritizing each other in a world full of distractions. You can start to manage thirds in your relationship by thinking of all the thirds in your life and then rating them based on how much of an impact they have on your relationship and stress levels.

5. Create a system.

Stress makes life feel chaotic. Developing a system can help create a sense of stability and calm. To start a system, you’ll need to make your stress visible. This means sitting down with your partner and writing out the stressors, big and small, that you are experiencing. Then, create three metaphorical baskets: shedding, preventing, and adapting.

Think about the stressors on your list that you can shed. This might be anything you are paying for that you don’t need. Tasks that you can outsource or unnecessary obligations. Put everything on your list that fits this definition into the shedding category and commit to unloading each item in that basket.

Next, look at your list and identify which stressors could have been prevented. Maybe you are stressed each morning and arguing with your partner because the kids never get out the door on time. Consider if this stressor could be prevented by putting out clothes the night before or making lunches ahead of time. Anything that could be prevented by planning and systemizing should go into the prevention basket.

Finally, add any stressor that you have no control over to the adapting category. While you might not be able to throw them into the trash bin or prevent them with good planning, you can still change the way they impact your well-being. This is where self-regulation and co-regulation skills and a strong commitment to having each other’s backs come into play.

In this way, couples can respond to and grow from life’s difficulties as collaborators, helping each other feel safe and secure in an otherwise chaotic world.

To listen to the audio version read by author Elizabeth Earnshaw, download the Next Big Idea App today: