Nadina Galle, Ph.D., is an ecological engineer, technologist, podcast host, and keynote speaker, best known for popularizing the “Internet of Nature.” She has received both academic and entrepreneurial awards, including a Fulbright scholarship for a fellowship at MIT’s Senseable City Lab, where she still holds a research affiliation. She was named one of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 and recognized as a 2024 National Geographic Explorer.

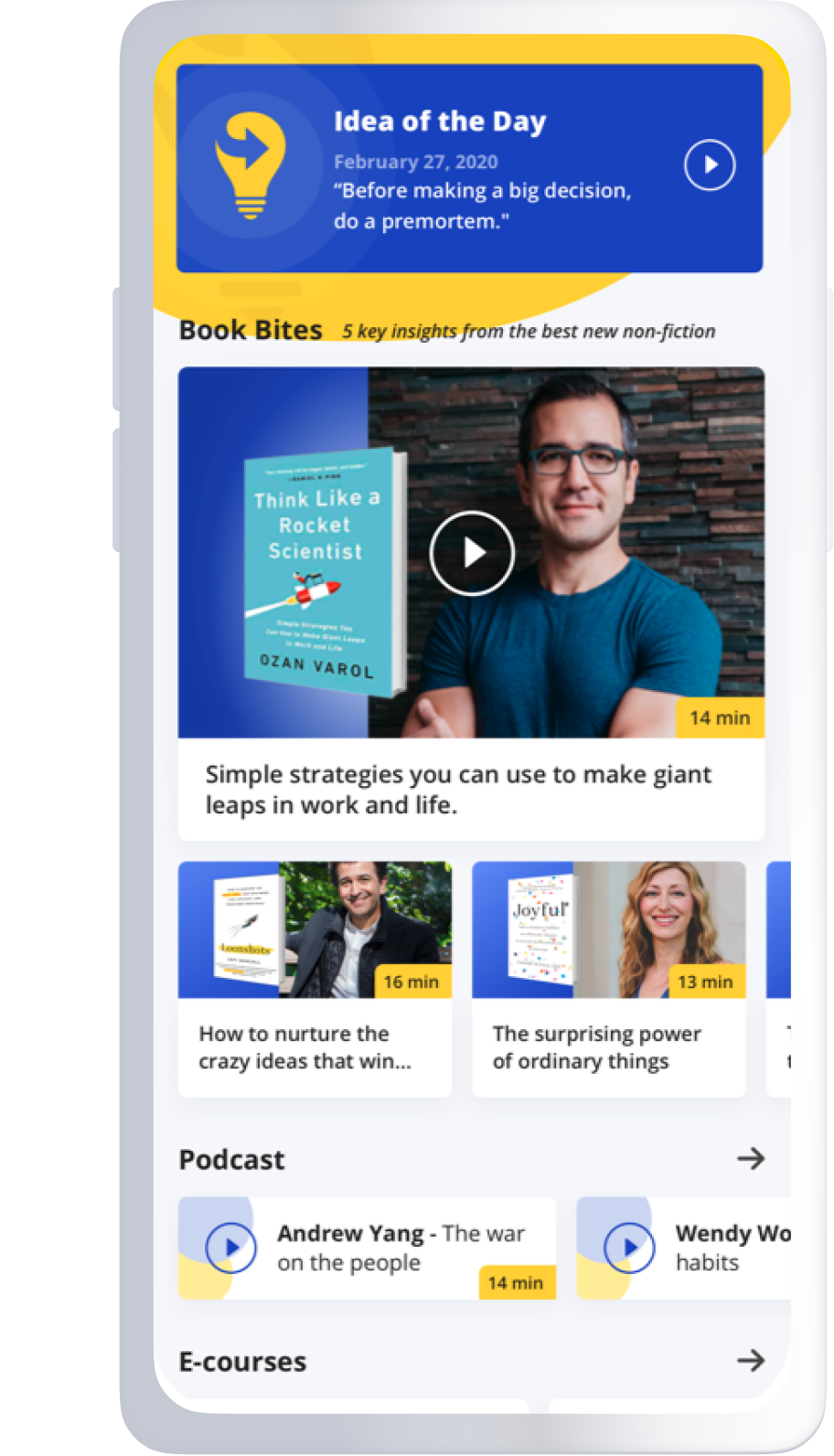

Below, Nadina shares five key insights from her new book, The Nature of Our Cities: Harnessing the Power of the Natural World to Survive a Changing Planet. Listen to the audio version—read by Nadina herself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Nature counts in cities—in fact, it may count more.

The Nature Pyramid, conceived by Timothy Beatley and Tanya Denckla-Cobb, emphasizes regular exposure to nature across different tiers: daily visits to local parks and green or blue spaces, weekly excursions to larger natural areas, monthly outings to wild places, and yearly extended stays in true wilderness.

However, I argue the foundation of this pyramid—daily interactions with nature—is equally crucial as the pinnacle. Research strongly supports the idea that proximity to nature influences health. A 2019 meta-analysis aggregating data from nine prominent studies involving over eight million subjects revealed a significant association between increased greenness around homes and reduced premature death. Each incremental increase in vegetation within 500 meters of a residence correlated with a four percent decrease in premature mortality risk.

To leverage these health benefits, we must identify the types of nature that best support human well-being, map their locations, and encourage people to spend more time in such environments. This is where technology plays a pivotal role.

Satellite imagery and comprehensive datasets, encompassing various factors like air and noise pollution, parkland availability, water bodies, and tree cover, enable us to distill the components of health-supporting nature into a single variable. By aggregating this data at the Census tract level, approximating neighborhood size, we can obtain a detailed picture of where nature thrives and is lacking nationwide.

But quantifying nature also exposes sobering realities, revealing how densely populated neighborhoods often lack green spaces and how the least affluent city residents have limited access to nature’s health benefits. Nevertheless, it offers insights into which urban areas would benefit most from nature infusion.

Large tree-planting foundations, which allocate significant funding to tree-planting initiatives globally, can utilize this data effectively. For instance, if a donor proposes planting trees in an affluent area, the data can support the argument that these trees would yield greater benefits in other locations.

2. Urban trees rely on us as much as we rely on them.

One of my mentors, renowned tree biologist Dr. Andrew Hirons, once told me, “Don’t tell me how many trees you planted today; tell me how many will still be there in 50 years.” We live in an era of million, billion, and even trillion tree-planting campaigns. However, simply focusing on planting trees in large quantities might divert attention from the critical need to preserve existing trees, particularly the older ones.

Older trees tend to have larger crowns due to their size. These expansive canopies expel more oxygen, increase property value, provide ample shade, purify the air, and offer abundant habitat for wildlife. Remarkably, they significantly impact human health and well-being as well. A recent study by KU Leuven concluded that larger crown volume was associated with reduced medication usage. Even more intriguingly, a larger crown volume across fewer stems proved more beneficial for cardiovascular and mental health than a similar volume spread across more stems. Simply put, a street with fewer but grander trees promotes better health.

“Simply focusing on planting trees in large quantities might divert attention from the critical need to preserve existing trees.”

From an ecological perspective, it’s logical. In terms of health, it checks out. Economically, it also makes sense. Research since 2004 has consistently shown that bigger trees equate to bigger savings. The U.S. Forest Service Center for Urban Forest Research highlighted that the benefits of large-statured trees far outweigh the costs of their maintenance, sometimes by as much as eight to one.

Indeed, large-crowned species such as London planes, beech, and oak require costly, meticulously designed tree pits to flourish. This is especially true when surrounded by pavement. However, the costs incurred are more than compensated when we accurately value the benefits these trees provide.

Advancements in technology are reshaping how we evaluate urban forestry success—not in terms of saplings planted, but in the year-over-year growth of crown volume. For instance, Lidar mapping generates a 3D map of a city’s trees—a digital replica of its urban forest. This technology can swiftly map a city’s trees with objective, reproducible measurements—a task that previously consumed years and was prone to human error and subjectivity.

This data allows city councils to objectively calculate the tree benefits they’re missing out on—whether that’s cooling, shade, or improved air quality. These ecosystem services are invaluable contributions trees provide that we can quantify. So, if a new development plans to remove ten trees, the city council can accurately assess what will be lost and hopefully take action to prevent further loss of old trees.

3. Harnessing nature’s buffer against Mother Nature’s fury.

In the intricate dance between urbanization and the natural world, it’s easy to overlook the profound irony: Nature itself often holds the key to protecting us from the very forces it unleashes. As cities expand and climate change intensifies, the need for green infrastructure becomes increasingly evident. Far from being just a pleasant aesthetic addition, nature in urban spaces serves as a critical buffer against the wrath of Mother Nature.

One of the most pressing challenges exacerbated by urbanization is flooding. Impermeable surfaces like concrete and asphalt dominate cityscapes, leaving rainwater with nowhere to go but into overwhelmed stormwater systems. However, strategically integrating nature into urban design—such as green roofs, permeable pavements, and bioswales—creates natural pathways for rainwater absorption and filtration. These green solutions not only reduce the risk of flooding but also replenish groundwater reserves and mitigate pollution runoff, safeguarding both infrastructure and ecosystems.

Moreover, the menace of wildfires looms larger with each passing year, fueled by climate change and urban sprawl. Yet, managed vegetation—properly spaced trees, fire-resistant plants, and strategic forest management—acts as a vital barrier, slowing the spread of flames and reducing their intensity. By creating defensible spaces and firebreaks, green infrastructure not only protects lives and property but also preserves biodiversity and ecosystem health.

“These green oases are essential for protecting vulnerable populations and maintaining livable urban environments in a warming world.”

Beyond these tangible benefits, nature in cities fosters resilience in myriad ways. Increased greenery supports diverse wildlife populations, promoting ecosystem stability and enriching urban biodiversity. Moreover, access to green spaces enhances public health and well-being, offering sanctuary from the stresses of urban life and fostering physical activity and mental rejuvenation.

Perhaps most urgently, as heat waves become more frequent and severe, urban greenery emerges as a literal lifesaver. Trees, parks, and green corridors provide critical cooling, mitigating the urban heat island effect and offering refuge from sweltering temperatures. These green oases are essential for protecting vulnerable populations and maintaining livable urban environments in a warming world.

In this symbiotic relationship between cities and nature, the irony is clear: By embracing and integrating nature into our urban landscapes, we fortify ourselves against the very forces we seek to tame. Investing in green infrastructure is a necessity for building resilient, sustainable cities that thrive in harmony with the natural world.

4. Time outside creates greener neighborhoods.

When people ask me about the importance of spending time outdoors, I often find myself providing reductionistic, quantifiable answers that science has provided. With over 500 studies showcasing the benefits, ranging from bolstering the immune system and alleviating anxiety in adults to enhancing eyesight and fostering brain development in children, the advantages are undeniable.

But framing the question as why is it so important to get outside? misses the broader issue. Humans evolved to inhabit the outdoors, but we now spend 93 percent of our time indoors. The better question is: what are the consequences of this indoor-centric lifestyle?

This shift indoors has broader implications, notably in how rapidly we destroy ecosystems to accommodate human development, such as housing. Chesterton’s Fence is a cautionary principle that suggests you shouldn’t destroy what you don’t understand. In this case, if I were to urge against destroying an ecosystem, it’s not my role to explain why these ecosystems are essential. The burden lies on those choosing to alter or destroy them to understand their significance.

However, with humanity now spending the majority of its time indoors, I fear we’ve reached a point of no return. Convincing people to go outside is wildly challenging. To address this, technology has stepped in with innovative solutions. Just as fitness trackers like Fitbit revolutionized physical activity, emerging apps provide personalized insights into our outdoor interaction. By monitoring our time spent indoors versus outdoors, these technologies serve as gentle reminders to prioritize outdoor time and form healthy habits.

“Humans evolved to inhabit the outdoors, but we now spend 93 percent of our time indoors.”

While we intuitively know that nature is beneficial, until recently, there hasn’t been a convenient way to measure or motivate outdoor exposure. These emerging apps bridge this gap by providing tangible data and encouragement. By promoting more time spent outdoors, they aim to cultivate a greater appreciation for nature, potentially leading to increased support for public green spaces and nature-inspired design. Furthermore, understanding how different outdoor environments impact our well-being allows us to optimize our experiences for maximum benefits.

In essence, while the idea of using technology to encourage outdoor activities may seem counterintuitive, it serves as a stepping stone toward a healthier and more sustainable future. One day, immersing ourselves in nature will be second nature, ingrained in our culture, as it once was. But until then, these tools offer a practical means to enhance our well-being while nurturing our relationship with the environment.

5. Used wisely, technology can help raise future naturalists.

Indoor living often translates to indoor childhoods, reshaping children’s relationship with nature. Closed school buildings and sedentary home environments deprive future generations of the innate physical and psychological health benefits of nature, leading to what author Richard Louv terms Nature Deficit Disorder, which has become increasingly prevalent among children.

The primary challenge in addressing Nature Deficit Disorder in cities is ensuring access to nature—green spaces, parks, outdoor playgrounds—in neighborhoods, schools, and backyards. Better data, on-the-ground tools, and innovations can help prove the return on investment in climate, health, and well-being benefits, enabling more nature in urban areas.

However, once children have access to nature, can technology enhance their appreciation of it without disconnecting them from its wonders? In today’s digital age, screens can seduce young minds, but they can also serve as gateways to exploring nature. Digital tools and apps can inspire environmental stewardship by providing information, fostering creativity, and educating about nature’s vital role in mental, physical, and spiritual well-being.

For example, apps like Seek by iNaturalist can assist children in identifying plants and animals during outdoor adventures, while augmented reality games can provide educational opportunities, helping them learn about their surroundings and fostering a sense of wonder and connection. For me, as a new mother, this academic interest has become somewhat of a personal mission: to find a delicate balance between technology as a supplement to nature, not a replacement for it.

Fostering what Richard Louv calls a “hybrid mind” in children means nurturing both their tech-savvy abilities and an appreciation for nature’s interconnectedness. It involves blending the digital world with outdoor experiences, leveraging humanity’s knack for tool-making. Children who embrace this mindset will grasp their societal role, cultivate a deep love for nature, and refine problem-solving skills vital for life’s hurdles.

In the fusion of technology and nature lies the blueprint for a brighter future—a world where children experience both the wonders of the digital realm and the awe-inspiring beauty of the natural world. As we embark on this journey toward a “hybrid mind,” let’s remember that our actions today shape the world our children inherit.

To listen to the audio version read by author Nadina Galle, download the Next Big Idea App today: