Callum Robinson is a designer and woodworker. He has worked for clients that range from local families to some of the world’s most iconic luxury brands. He is creative director at Method Studio, the company he established with his wife.

What’s the big idea?

The life of a woodworker demonstrates the joys and challenges of what it means to work with your hands in our modern age. From the intimate processing of their materials, creative designs, engineering strategies, and magnetic artistry, the work of craftsmen fortifies communities and the generations to come.

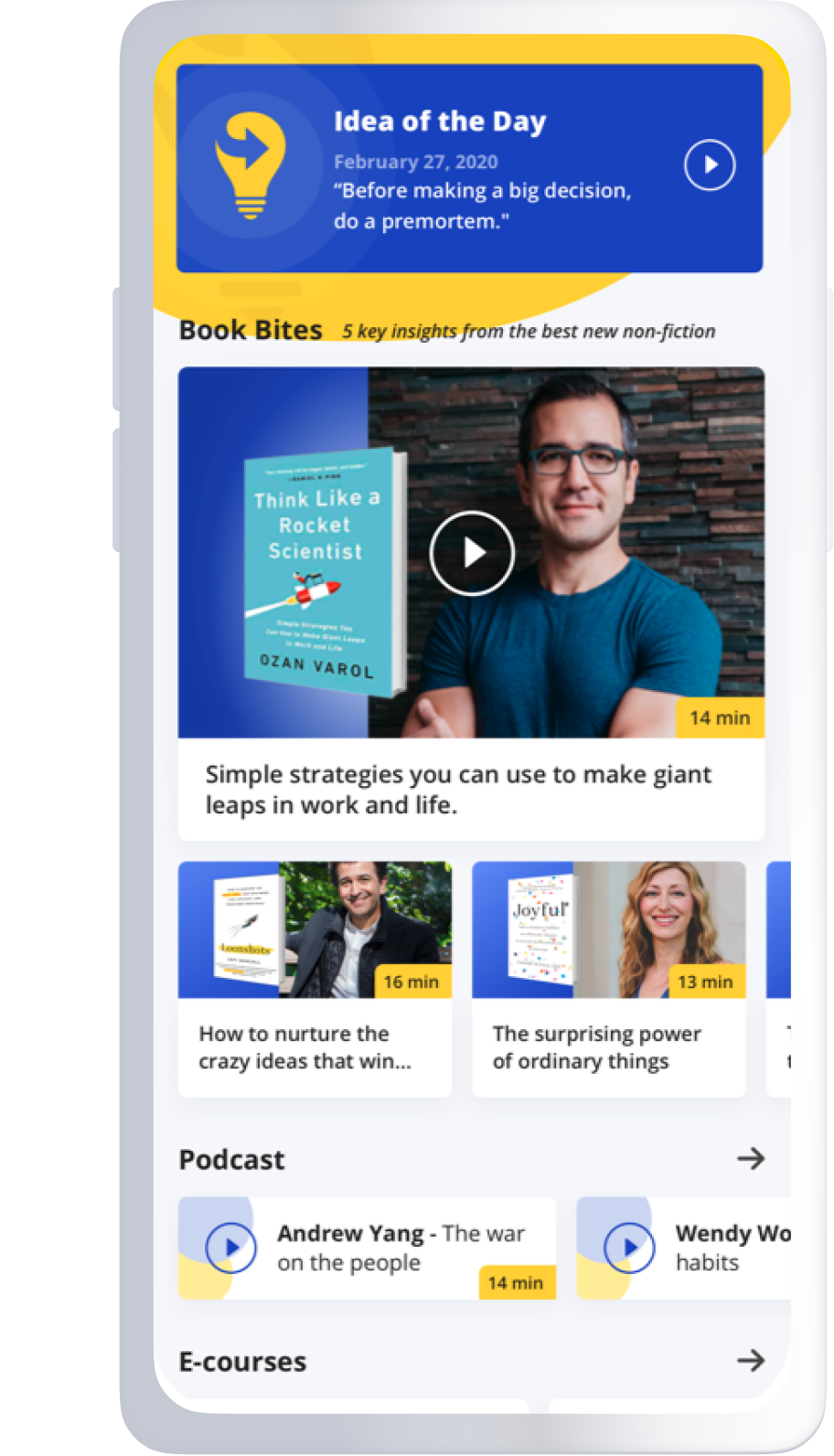

Below, Callum shares five key insights from his new book, Ingrained: The Making of a Craftsman. Listen to the audio version—read by Callum himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Wood is a connection to time and place.

Whenever I run my hands over a slab of timber, like at a sawmill where I often handpick boards for projects, I look for a variety of things: size, grain feature, and richness of color, whether it has cracks or splits or rot, the board’s density and weight, and the tell-tale twists of lurking tension. If a tree has spent its life stooped against strong prevailing winds and developed thick muscular tension-wood to compensate, a sawcut might begin to close almost immediately around a powerfully spinning blade—and that I do not want. With all these practical considerations tumbling in my head, it’s all too easy to forget what I am really seeing, or indeed, what it is that you are seeing whenever you sit down at a wooden table or run your own hands over the arm of a wooden chair.

Wood isn’t just tactile and beautiful—not to mention the world’s most sustainable building material—it’s a unique record, like a painstakingly gradual time-lapse photograph. Every difficult year, every drought, every flood, all the minerals and pigments leach up from the spot where a tree took root and visually record its history. Rippling shadows of a woodworm’s pinhole excavations, the relentless effort required to hold up those mighty limbs, and the torturous scarred stains from a barbed wire choker oh-so gradually absorbed. It’s all there, folded into the heartwood. Centuries of character, as individual as a fingerprint, written in the figure of the grain and revealed by the teeth of the saw.

2. There’s more to chairs than meets the eye.

It’s human nature to take the things we see every day for granted, and few objects have become quite so invisible as furniture. But if you spend your time designing, making, or repairing furniture, you start to see things differently—perhaps especially when you work with wood. Rarely is this rendered more starkly than with the kind of furniture you may be sitting in right now.

Think for a moment about the last time you leaned back deeply in a wooden chair, tilting it up onto two legs, perhaps in a manner that might induce a teacher to shout at you. Just imagine the forces at work on the wood and the joints. Tables need only withstand their own weight and that of the dinner service, but chairs must be built to withstand the forces of a fully grown adult lounging in them, day after day, year after year, stressing the connections and flexing the timber.

“Making chairs is as much an exercise in engineering as it is in furniture design.”

To give their construction strength, chairs often need as many, if not quite a few more, components and joints than the tables they gather around. That’s in addition to being comfortable, ergonomic, lightweight, and elegant. Making chairs is as much an exercise in engineering as it is in furniture design. But no matter how fiendishly tricky they are to create, how many more parts and joints and extra costs, such as upholstery, may be involved in their manufacture, they must be economical, too. Thanks to their scale and ubiquity, the sheer number of alternatives on the market, and the volume that often needs to be bought all at once, the price of a chair is always expected to be a fraction of a good-quality table. There’s even more to chairs than meets the eye.

3. There has never been a better time to explore the world of design.

Right now, this minute, there is an almost unimaginable quantity of exciting design work. Historical, contemporary, futuristic, sculptural, mechanical, organic, and digital—work that, just a generation ago, would have been almost impossible to find. Use it. Pore over books and magazines, get online, read interviews with designers in different fields, and discover what moves them to do what they do. Scroll (God help you) through social media. Collect, curate, and digitally scrapbook. Train the algorithm to feed you something nutritious.

Then, go track down physical examples. Learn for yourself that, like iconic artwork, architecture, and beautiful people, well-designed and well-crafted objects have a magnetism that can only be felt in person. The more of it you expose yourself to, the better.

Visit exhibitions, galleries, museums, and degree shows. Seek out country houses, design stores, and expensive hotels. Get out into nature and enter the Natural History Museum. In all these places, get up close, get down on your knees even, and really look. Unearth the things you love, the things that speak to you, and ask yourself why they work—not just how. Seek the seeds of inspiration, hybridize, and nurture your own creative voice because the world needs all the makers it can get.

4. The true value of handmade is mostly hidden.

Handmade has become a pervasive term, often uttered in the same breath as artisanal and boldly slapped onto scores of consumer products. Despite its ubiquity, the idea of buying or commissioning something genuinely handmade by a local craftsperson is a daunting prospect for most people. It’s often a step into the unknown, requiring trust and patience (my father is a Master Wood Carver, and his waiting list is several years long). It can be costly compared to buying something off-the-shelf from well-known manufacturers. But price and value are not the same thing.

A finely crafted handmade wooden table, for instance, can last for hundreds of years. Take good care of it, and your children’s children might well be banging their knives and forks on it long after you’re gone. Unlike so much of the fast furniture churned out these days, not only will you be able to maintain and repair it, but critically, because it will mean something to you, you’ll want to care for it.

“Price and value are not the same thing.”

More than that, you’ll be supporting a maker who may be leveraging thousands of hours of accumulated craft skills—skills they may well pass on and that we must not lose. You’ll be supporting the sawmill, and perhaps the tree surgeon who felled the tree, and everyone they will ever teach their trades. You’ll be investing in your community’s richness, sustainability, pride, and self-reliance. Chances are, you’ll never need to buy another table for the rest of your life.

5. Making things can change your life.

When I was a teenager, drifting aimlessly through life with only the vaguest inkling of what confidence or self-worth felt like, I had the good fortune to drift into woodwork. Unlike the classroom, the sports field, or my booze-blunted social life, becoming engaged in the physical act of creation changed everything for me. In a world full of distraction, it gave me purpose and focus, helping me forget about myself for a while and giving me something I could be genuinely proud of. Making something useful, sometimes even beautiful, for someone else gave me a way to show them, even if I couldn’t tell them, that I cared.

Time and again, from the very young to the very old, and no matter how simple the project is, I’ve witnessed the power that making things can have to make people happy. Engaging with the natural world through manual labor speaks to something ancient in all of us, and it’s something that can forever change our relationship with the objects around us. If you’ve ever harbored dreams of getting your hands dirty, whatever the medium, today’s the day to make them a reality. Making things might well change your life, too.

To listen to the audio version read by author Callum Robinson, download the Next Big Idea App today: