Nicholas Carr has written several books about the human consequences of technology, including the Pulitzer Prize–finalist The Shallows. He was recently a visiting professor of sociology at Williams College, and earlier in his career, he was executive editor at the Harvard Business Review. In 2015, he received the Neil Postman Award for Career Achievement in Public Intellectual Activity from the Media Ecology Association.

What’s the big idea?

The great tragedy of communication is that the more we have, the more discord it sows. Despite generations of repeated hope that world peace awaits on the other side of faster, more frequent contact, the reality is that history and psychology tell a different story.

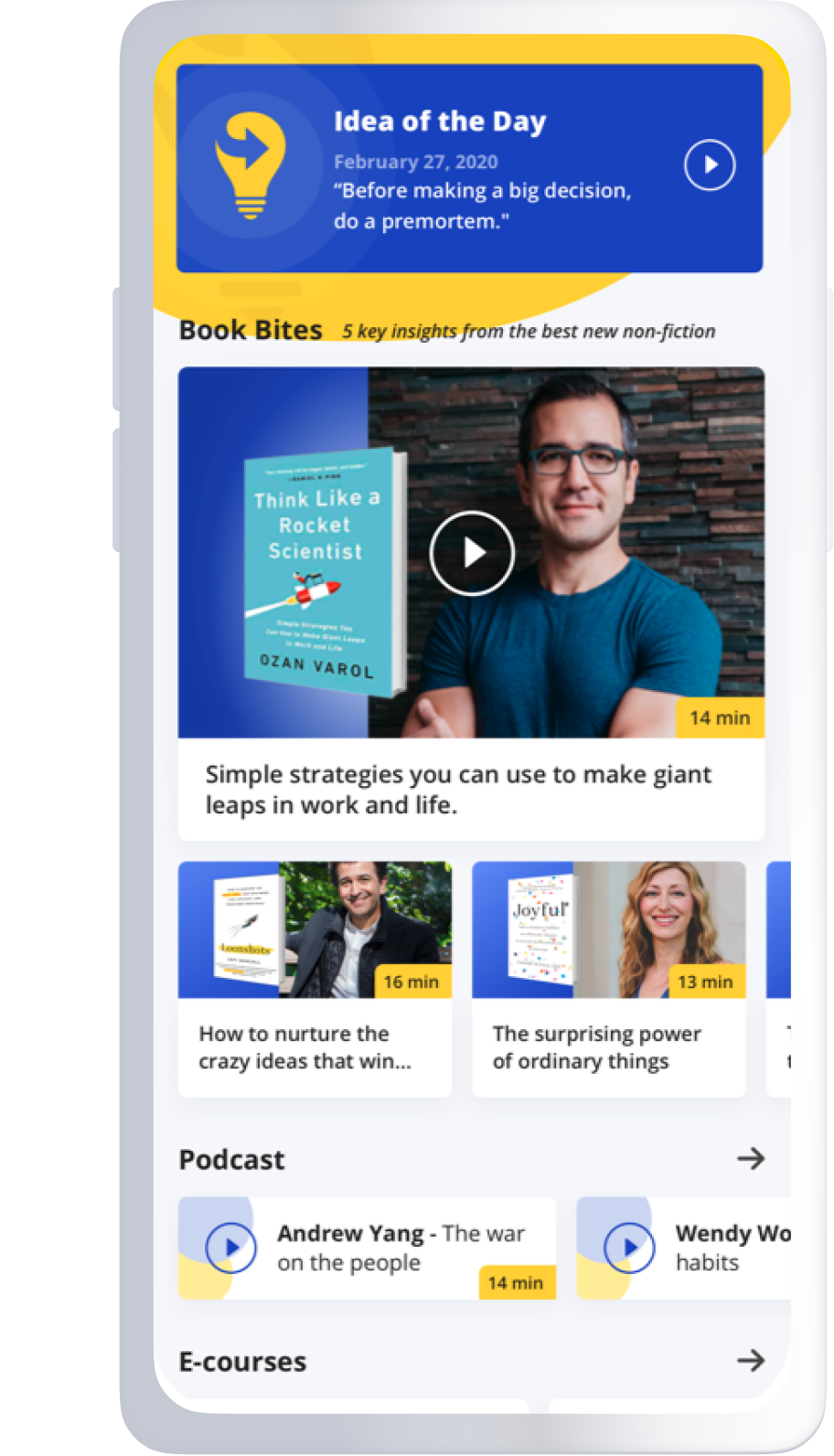

Below, Nicholas shares five key insights from his new book, Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart. Listen to the audio version—read by Nicholas himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. More communication can mean less understanding.

It sounds like a paradox. Ever since the great Enlightenment philosophers started dreaming of a world-encompassing Republic of Letters, society has dedicated itself to increasing the efficiency of communication—its speed, volume, and reach. If communication is good, the assumption goes, more of it must be better.

When the telegraph arrived in the 19th century, and messages could suddenly travel at the speed of electric current, everyone rejoiced. Civilization seemed on the verge of a utopia of perfect understanding. “A new channel of blessing has been opened for the world,” declared a prominent Boston minister in a widely circulated sermon. The system’s “most remarkable” consequence, he went on, “will be the approach to a practical unity of the human race; of which we have never yet had a foreshadowing, except in the gospel of Christ.”

His words would be echoed repeatedly as telecommunications and broadcasting advanced. Nikola Tesla, in an 1898 interview about his plan to create a wireless telegraph, said that he would be “remembered as the inventor who succeeded in abolishing war.” Not to be outdone, his rival, Guglielmo Marconi, proclaimed in 1912 that his invention of radio would “make war impossible.”

They were tragically wrong. In 1914, the First World War broke out. Its start was hastened by the new technologies of communication. After Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated on June 28, hundreds of urgent diplomatic messages raced between European capitals through newly strung telegraph and telephone wires. The rapid-fire dispatches quickly devolved into ultimatums and threats. Rather than calming the crisis, they inflamed it. “Diplomats,” writes historian Stephen Kern, “could not cope with the volume and speed of electronic communication.” Diplomacy, a communicative art, was overwhelmed by communication.

Despite the thrilling, relentless expansion of people’s ability to exchange information, the twentieth century turned out to be the bloodiest in history. We had been telling ourselves lies about communication—and about ourselves.

2. The more we learn about other people, the more likely we are to dislike them.

We want to believe that communication brings us together, on a personal level as well as a societal one. The evidence tells a different story. In 1976, three professors from the University of California San Diego studied a large condominium development in Orange County, interviewing residents and carefully charting their relationships with neighbors. They found that the nearer people live to each other, the more likely they are to be friends. That was hardly a surprise. Not only was it commonsensical, but it was also consistent with a well-established psychological principle called the proximity effect.

But the researchers discovered that living close together also often had the opposite effect. It turned people against each other. While close neighbors were much more likely to be friends, they were also much more likely to be enemies. In fact, proximity bred animosity more often than it did affection.

“While close neighbors were much more likely to be friends, they were also much more likely to be enemies.”

The reason lies in what the researchers termed environmental spoiling. The closer you live to another person, the more exposed you are to their habits. If you find those habits irritating, you’ll resent that person for degrading your surroundings. And because proximity guarantees those irritating habits will always remain in view, your resentment and antipathy will fester.

A later series of experiments revealed that a similar dynamic plays out as we receive more facts about other people. Sometimes, we end up liking a person more as we learn more about him or her. More often, though, we end up liking the person less.

The explanation lies in what the researchers called dissimilarity cascades. Perceptions of similarity play a decisive role in determining whom we like and whom we don’t. We have a bias to like people who seem similar to us and dislike those who seem different. The experiments revealed that the tendency toward disliking is even stronger than the tendency toward liking. As soon as the study participants were exposed to a character trait indicating that a person was unlike them in some way, they began to emphasize evidence of dissimilarity more than evidence of similarity. Differences became more salient and commonalities less salient as personal information increased. Familiarity breeds contempt.

3. Social media is an ideal vector for enmity.

There may not be garbage cans or dog poop in the virtual world, but there’s plenty of environmental spoiling. Everybody is in everybody else’s business all the time. The internet turns us all into Peeping Toms, peering into the lives and thoughts of others.

It also turns us into blabbermouths. Social networks like Facebook, X, and Instagram encourage constant self-disclosure. Because status is measured quantitatively in numbers of followers, friends, likes, and retweets, people are rewarded for broadcasting endless details about themselves and their opinions. In the physical world, we remain present even when we’re quiet. In the virtual world, we don’t. To shut up is to disappear. One study found that people share four times as much information about themselves when they converse through computers as when they talk face to face.

As all this personal information swirls around the net, people find a lot of evidence of what they have in common with others—and a lot of evidence of what they don’t. They see likenesses, and they see differences—and over time, they begin to place more weight on the differences. It’s hard to imagine a communication system more perfectly geared to initiating and propagating dissimilarity cascades than social media. The information that circulates through a social network can act as an attractant. More often, it’s a repellent.

Now, that’s not to discount the close bonds many people have formed online. Facebook posts have rekindled friendships. Snaps have spawned romances. Exchanges of tweets have opened deep conversations. TikToks have inspired communal joy. Many people who feel isolated or uncomfortable in their physical surroundings have found companionship and a sense of belonging in the internet’s vast, disembodied social scene.

“People share four times as much information about themselves when they converse through computers as when they talk face to face.”

But social media’s benefits, as real and welcome as they are, shouldn’t blind us to the deeper ways digital technology is changing social dynamics. The discoveries psychologists have made about the fraught nature of human relationships reveal how ill-suited the human psyche is to our new media environment. As connections multiply and messages proliferate, relationships get stretched thin. Mistrust spreads. Antipathies mount. We often feel an oppressive sense of what psychologists call digital crowding, and that, in turn, can breed stress and provoke antisocial reactions. When there’s too much communication, it begins to undermine the social and personal qualities that foster it.

4. The internet cannot be fixed.

We continue to resist the historical and psychological evidence of the problems communication technologies cause. In the 1990s, when the internet was new, we imbued it with our utopian dreams for social harmony—just as our ancestors had done with telegraph and telephone systems. The prominent British intellectual Frances Cairncross declared in her influential 1997 book The Death of Distance that the internet’s effect “will be to increase understanding, foster tolerance, and ultimately promote worldwide peace”—words that echo the rhetoric of Tesla, Marconi, and others a century earlier.

Even today, with the evidence of social media’s destructive consequences in clear view, we’re reluctant to blame the technology. Instead, we blame the myriad problems on technology companies and their algorithms. We believe that the companies, in their pursuit of profits, perverted the net. We don’t want to admit that technologies of connection can tear us apart.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s a lot to criticize about Big Tech, and I certainly don’t let the companies and their leaders off the hook. But even if we dismantle Meta and Google, X and TikTok, the social problems won’t disappear. That’s because the problems stem from a fundamental conflict between digital technology and human nature.

Computers are designed to maximize the speed of data transfer, to shorten the delay between input and output. The more we rely on computer networks to mediate what we say, see, and think about, the more we have to adapt our thought, speech, and behavior to their characteristics and requirements.

“The human mind is and will always be ill-suited to the rapid-fire exchanges of information that characterize digital media.”

To keep up with the torrent of messages and other information, we have to forgo the slow, deliberate work of interpretation, analysis, and reflection. Instead, whether we’re thinking about people or political issues, we rely on snap judgments, biases, hunches—fast, reactive ways of thinking and perceiving. The human mind is and will always be ill-suited to the rapid-fire exchanges of information that characterize digital media. As with the diplomats before World War I, we’re overwhelmed with communication.

The internet is not broken. It’s operating exactly as it was designed to operate. It’s succeeding in making our dream of perfect communication—efficient, unfettered, immersive—a reality, even as it reveals the dream to have been a delusion all along.

5. Friction is good for you.

It may be too late to change the system. It’s not too late to change ourselves.

The overriding goal of software programmers has always been increasing efficiency by finding friction in some task or process and removing it through automation. That can bring many benefits. It can make hard chores easier. It can increase productivity in the economy. It can enable individuals to accomplish things they otherwise couldn’t.

As social media platforms were built, the focus was on increasing the efficiency of conversation and information exchange. Facebook’s empire was constructed by pursuing what Mark Zuckerberg famously called “frictionless sharing.” By letting high-speed computers orchestrate communication, vast numbers of people could exchange vast quantities of information instantaneously.

But efficiency is the wrong goal to apply to human communication and relationship-building. That’s been our great mistake: We’ve embraced a system that applies industrial objectives and measures to the most intimate and subtle human pursuits.

The friction we came to see as an obstacle to communication—the time it takes to write and mail a letter, for instance, or the effort required to go out and talk to people in person, or the expense of subscribing to a printed newspaper or magazine—was a good thing all along. Friction in communication requires us to think before talking, to listen carefully to others, and to impose discretion and deliberation on our media habits.

We need to pause and back up a bit. If you’re using the wrong tool for the job, and you know you’re using the wrong tool for the job, then the worst thing you can do is persist in using the wrong tool for the job.

To listen to the audio version read by author Nicholas Carr, download the Next Big Idea App today: