Michael Chad Hoeppner is a former Columbia Business School professor and the founder of a communication firm named GK Training. In his 15 years leading the firm, he has coached everyone from U.S. presidential candidates to high school students.

What’s the big idea?

“Don’t” is the worst advice. If someone tells you don’t say um, you’re probably going to say it because suddenly it’s the pink elephant you’re not supposed to think about. To improve public speaking skills, practice and preparation needs to train the body to speak well—not just the mind.

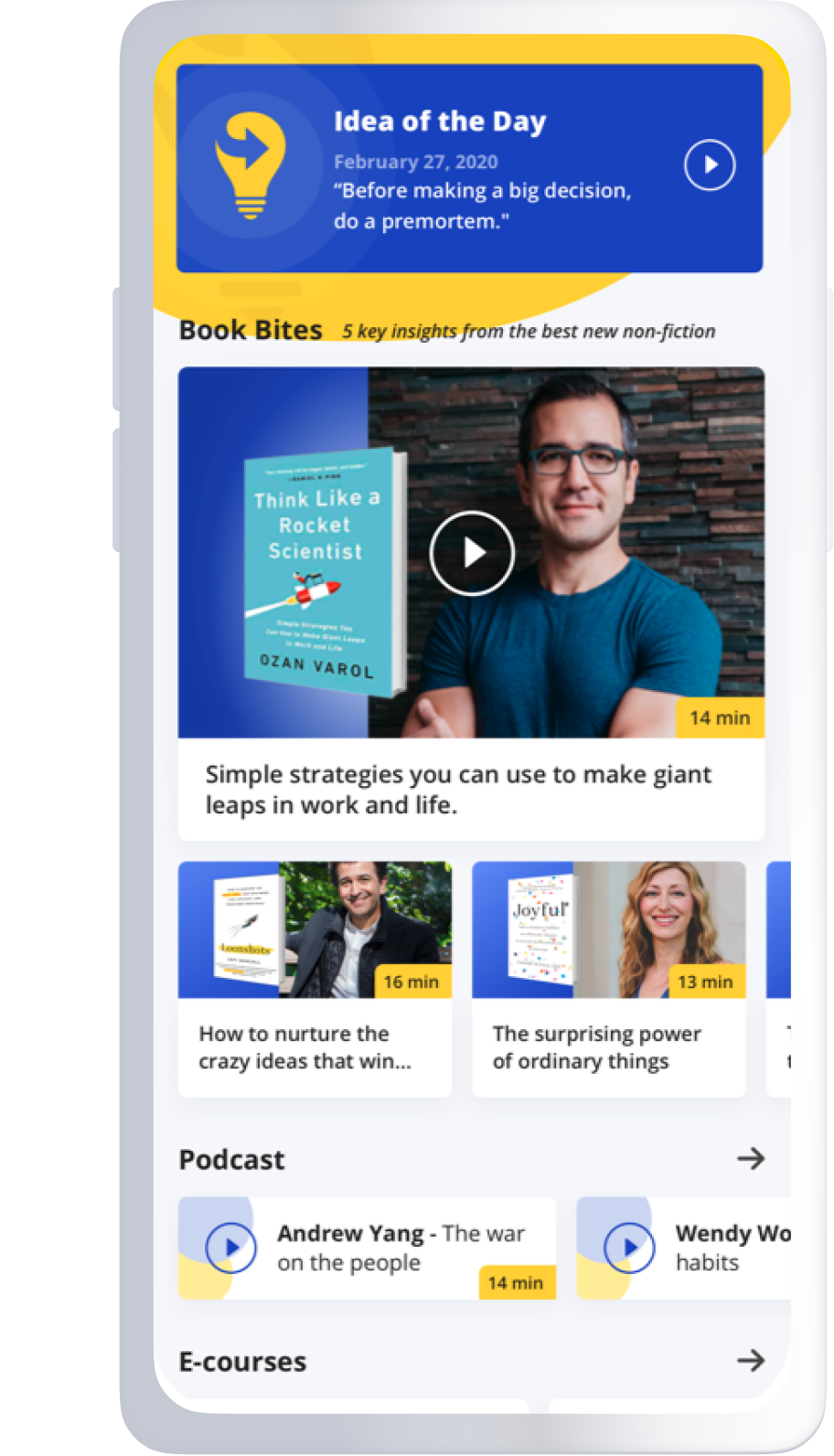

Below, Michael shares five key insights from his new book, Don’t Say Um: How to Communicate Effectively to Live a Better Life. Listen to the audio version—read by Michael himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Public speaking is everywhere.

I encourage my clients to eradicate the term public speaking from their vocabulary. Whether you’re addressing an audience of one or many, you are still communicating in public, not in a private, whispered exchange. I invite you to radically expand what counts as public speaking. Limiting this perspective is self-sabotage, which can have catastrophic consequences.

First, it robs you of countless daily opportunities to practice and refine your communication skills. Second, it perpetuates the harmful belief that public speaking is a rare, avoidable event reserved for so-called “naturals.”

It’s time to broaden your lens. You’re already public speaking—constantly! And you will continue to do so throughout your career. Improvement isn’t just possible, it’s transformative. With the right mindset and effort, you can grow your skills dramatically.

2. Much of what you have heard is wrong.

Far too often, people receive advice about speaking that is unhelpful or counterproductive. It typically falls into three problematic patterns:

- It triggers thought suppression. Have you ever been told, don’t be nervous, don’t use your hands too much, or don’t rush? If so, you’ve experienced thought suppression. The human brain is notoriously bad at this. The moment you hear don’t, your mind fixates on what you’re supposed to avoid—like the classic “Don’t think about a pink elephant” instruction.

Adam Galinksy (a colleague of mine at Columbia Business School) studies this phenomenon. When you tell your brain don’t, it zeroes in on the very thing you’re trying to suppress to distinguish it from everything else. This concept inspired the title of my book, Don’t Say Um. The title is a trick: while readers are drawn to learn how to stop saying um, the book reveals that the best advice is “Don’t listen to any advice that starts with a don’t.”

- It’s paired with vague, unactionable suggestions. This dynamic is so common that I’ve dubbed it The Don’t General. Here’s how it works: after the initial don’t, the advice is followed by a totally general suggestion—often signaled by the word just. Examples of these sweeping, unhelpful suggestions are: Just be yourself. Just take your time. Just command the room.

While these ideas might have good intentions, they lack specificity and practicality. Such advice leaves speakers feeling like failures when they inevitably can’t execute something so ambiguous. It’s not the speaker who has failed—the advice has.

- When the advice is actionable, it is often a mental instruction for a physical activity. We underestimate how physical the act of speaking is. We think of it as a cognitive activity, but it takes more than 100 muscles to do the miraculous act of turning air into sound and sound into words. If you’ve heard advice like “take a breath” or “speak slowly” and then been unable to execute, you’ve fallen into this trap.

We recognize this in other physical disciplines. No golf pupil would be satisfied with a pro who simply stated instructions but never actually had the amateur golfer practice with a club in their hands. We shouldn’t settle for similarly inadequate coaching when it comes to speaking.

3. Your preparation is probably wrong.

Before building better speaking habits, let’s talk about the preparation because there’s a good chance your current approach isn’t serving you. Most people prepare for speaking by writing. They spend excessive time perfecting scripts, outlines, or slides, but far too little time testing those words out loud. This common approach misses the mark for several reasons.

Try flipping the script with an exercise I call Outloud Drafting. Instead of starting with pen and paper (or keyboard), start with your voice. Open your mouth, and let words flow:

- Stand up.

- Ask yourself an open-ended, relevant question—out loud.

- If my audience takes away one thing from this presentation, what should it be?

- What is a story or example that illustrates my main point?

- Answer the question—also out loud.

Repeat the process several times. The first version will likely be rough. The second will improve. By the third attempt, you’ll notice a refinement in your ideas and delivery. Within minutes, you’ll have tested and polished some initial content for your presentation, with three major benefits over a writing-first approach:

- You’ll sound more natural.

- You’ll reduce anxiety. Outloud drafting replaces perfectionism with spontaneity.

- You’ll begin internalizing your material, without the rigidity of memorization.

Once you’ve drafted verbally, you can shift to writing, but only to jot down key bullet points for an outline. By starting with your voice, you’ll create a more dynamic, engaging, and authentic speaking experience.

4. Rely on your body, not just your brain.

Even with better preparation, you still have to deliver in the moment—often while battling old habits that hold you back. How do you break free from ineffective communication patterns and bad advice?

Over nearly two decades of coaching speakers in high-stakes settings, including presidential debates, I’ve developed a suite of exercises rooted in embodied cognition. These exercises use kinesthetic learning to disrupt unhelpful habits and replace them with new ones. With consistent practice, these new habits become second nature, forming muscle memory that naturally supplants the old patterns.

Challenges like speaking too quickly, mumbling, monotone delivery, clasping your hands, or aimlessly wandering the stage are all best addressed through this embodied approach. It’s not just about thinking differently; it’s about moving differently—even the minor muscle group movements that enable enunciation.

One example is a foundational drill designed to help speakers master an essential communication skill: pausing. Everyone understands that pauses are crucial. They give speakers a moment to collect their thoughts and allow listeners time to process what’s been said. I developed a kinesthetic drill called the GK Training LEGO drill.

“Everyone understands that pauses are crucial.”

The exercise relies on using Lego blocks, sticky notes, or other objects that can be manipulated. In the book, I even give readers an extra page they can rip out and tear into six pieces for this purpose. Lego blocks are preferable because interlocking them requires time and automatically enforces a pause. But any objects will do, provided discipline is maintained.

Gather the objects you are going to use, then determine some content you can speak about for a few minutes. Once you are ready to begin, pick up the first object and share only the first idea of what you want to say. You can consider this like a sentence; as soon as you reach the point where a period or semi-colon might appear, you must stack the Lego block in silence. Then, pick up the second block, maintaining silence. Once you have it aloft, you can speak aloud your second thought. At the end of that thought—in silence—stack the block on the previous. Silently pick up the third block. Once it is aloft, speak aloud the third thought. Continue this exercise, sharing one idea at a time with enforced silence at the end of each, until you have shared the entirety of what you want to say on the given topic.

5. You’re probably afraid of the wrong things.

Before I coached them, many of my clients lived in mortal dread of the wrong thing: making a mistake. When we are fully focused on our audience (and not ourselves), the very presence of mistakes vanishes entirely—not because we didn’t make them, but because we didn’t categorize them as such! We seamlessly, fearlessly, and immediately correct the mistake and continue communicating. The relevant thought experiment here is to imagine giving directions to a lost tourist. If the moment after an inaccurate instruction left your mouth, you realized it was wrong; you would never spiral into self-consciousness; you would just correct the inaccurate information and immediately get back to the task of helping the confused tourist.

The same principle can transform your communication life in situations that trigger self-consciousness, such as big speeches, presentations, pitches, interviews, meetings, events, and more. Instead of relying on the typical evolutionary threat responses of fight, flight, or freeze, I urge my clients to replace those three Fs with fake it, feature it, or fix it.

In the book, I provide readers with two pages of playing cards that display what I call Transparency Phrases. These are bits of meta-language that we all use intuitively and often unconsciously when we’re focused on our audience; language like, “Let me go back a moment,” or “Let me try that again,” or “put more simply,” or “oh, I can’t believe I forgot…I also want to say.” This is why I titled the chapter that contains these cards, “Recovering from Mistakes.” Notice that the title isn’t “Avoiding Mistakes.” Mistakes are a when, not an if. They are inevitable. The measure of your performance as a speaker is not based on whether you make a mistake but on how you recover from it.

To listen to the audio version read by author Michael Chad Hoeppner, download the Next Big Idea App today: